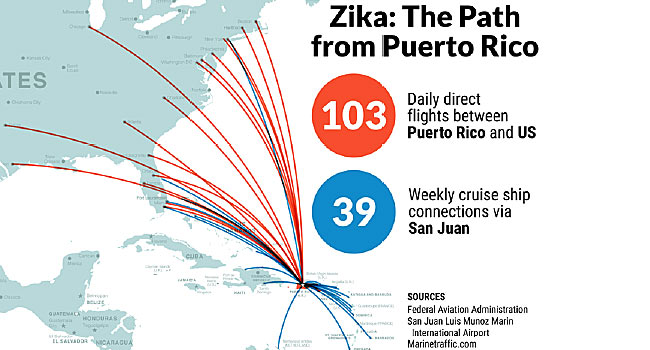

After reading Rosenberg’s foundational essays, we moved on to reading an essay I (Prof. Garriga-Lopez) co-authored with my friend Dr. Carlos Rodriguez-Diaz on zika virus in Puerto Rico. This essay, titled, “Becoming Endemic: The Zika Virus Epidemic and Gendered Power in Puerto Rico” was published by Lexington Books in an anthology edited by Shir Lerman and Ronnie Shepard called, Gender and Health in Contemporary Latin America and the Caribbean.

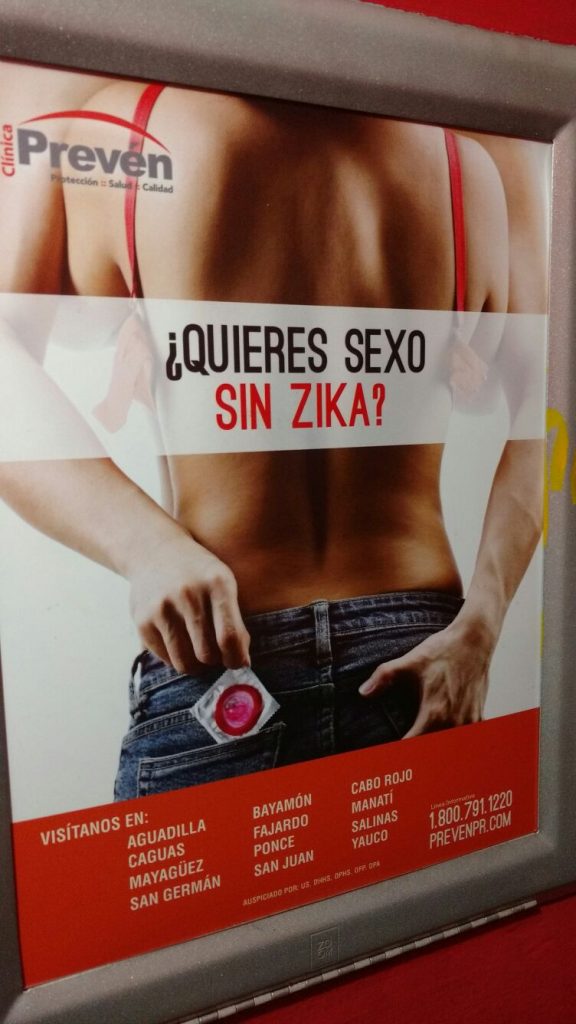

In this essay, Carlos and I analyze the Puerto Rican state’s response to the zika virus epidemic in Puerto Rico. We pay particular attention to the ways that the bodies of working class women of reproductive age were targeted as the main points of intervention because of zika’s effects on gestating fetuses and babies. We were concerned to show the ways that preventing zika virus infection thus became the responsibility of women, while the state provided few resources and no structural transformations. In 2017, we published this (open access) article in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, along with two other colleagues from Puerto Rico, but this one (“Becoming Endemic,” 2018) gave us an opportunity to attend to some of the gender-power-based dynamics we had observed.

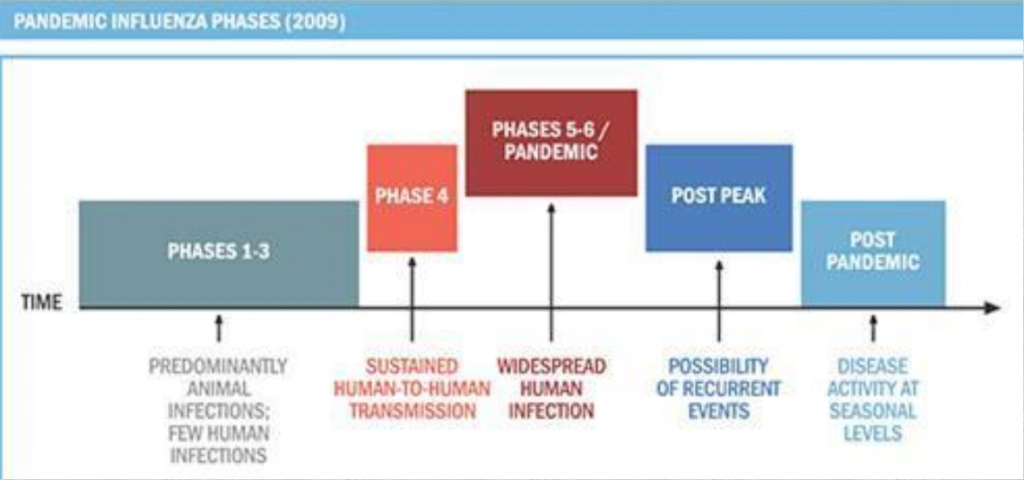

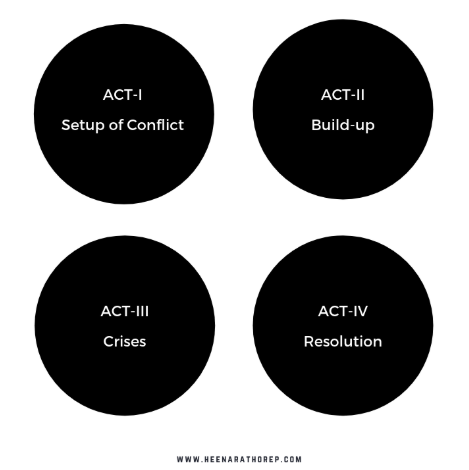

Additionally, in this essay we propose a fourth “act” to add to Charles Rosenberg’s dramatic reading of the stages of an epidemic. This fourth stage represents a narrativization of the epidemic, or a telling of “the story of what happened.” This fourth act is very important, for it represents the way that an epidemic is understood as part of human history. The story can be very different depending on who’s telling it and why, so this is also hotly contested territory.

Students engaged deeply with this text, raising many tough questions and pointing out that gender power and reproductive politics affects non-cis gender, non-heterosexual, and non-gender conforming people, as well as cis-gender, heterosexual women, and expressing a desire for more information about those effects. I recorded two videos in response to student comments and questions, which you can see below.

As a bonus, you can also check out this video art I created in 2016 about zika virus in Puerto Rico.

Did you or someone you know experience zika infection? Or is there something about this reading that you would like to remark on? Feel free to leave your comments or questions in the comment section below!